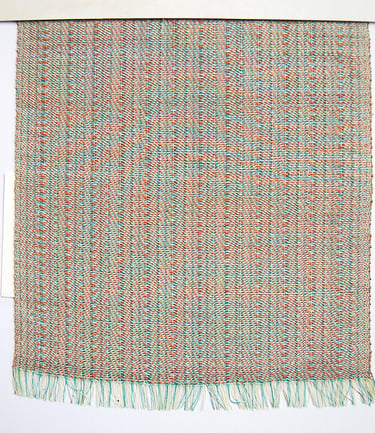

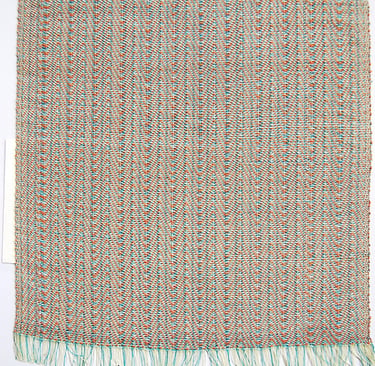

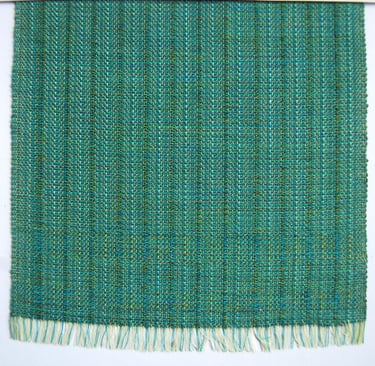

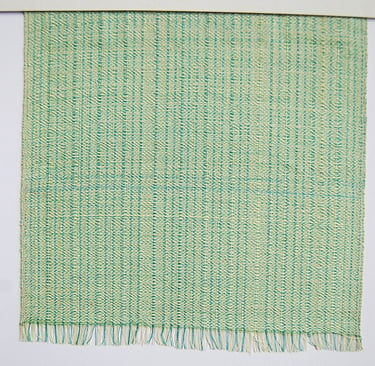

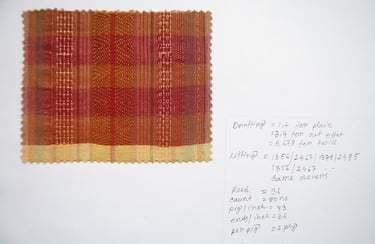

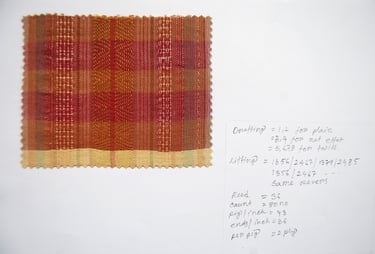

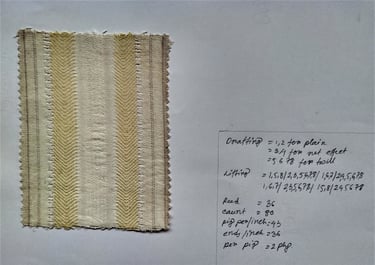

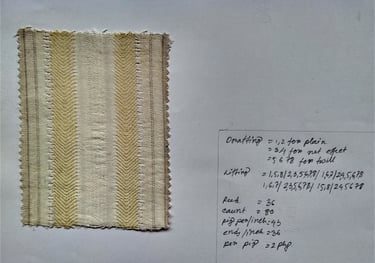

Tite - untitle

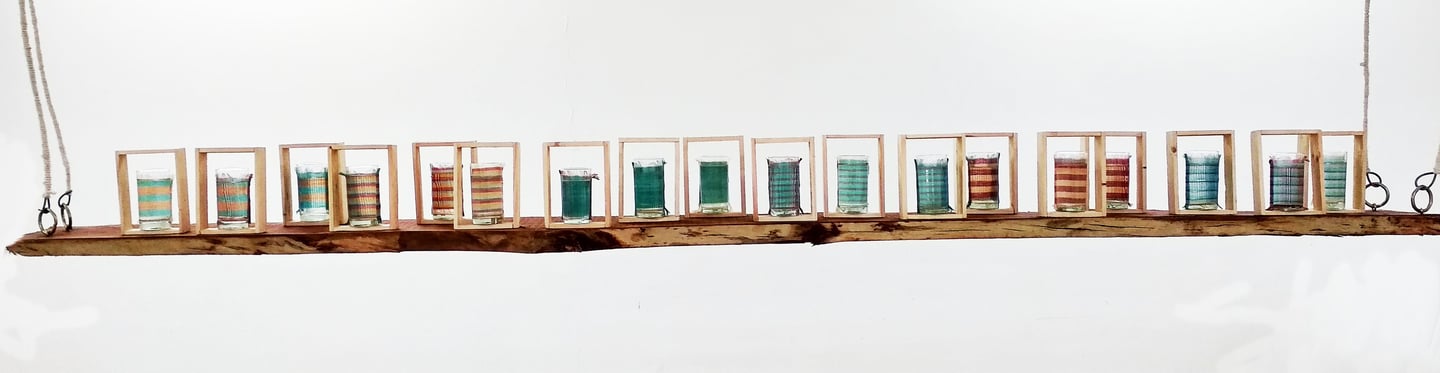

Medium - Weaving & instalation

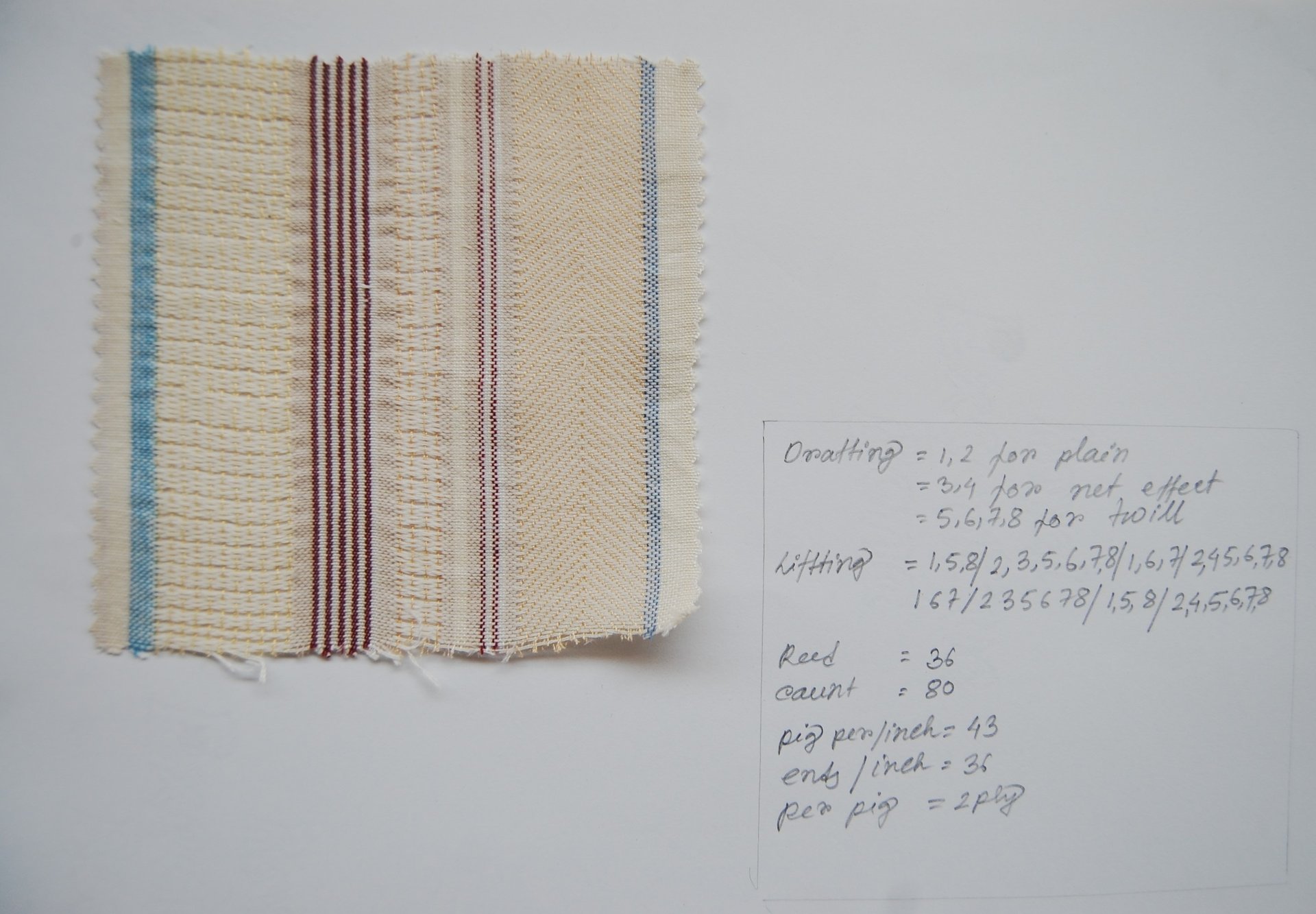

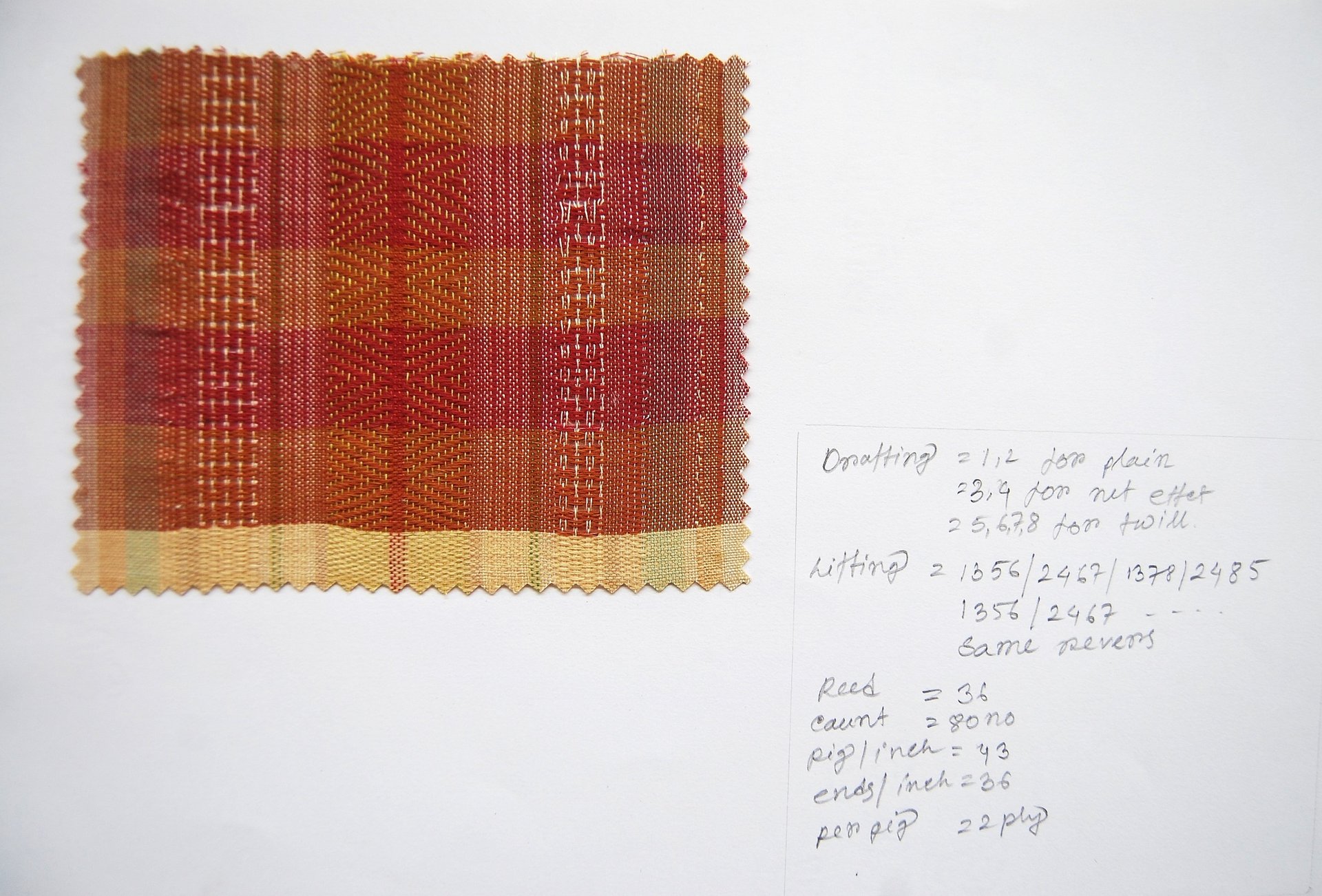

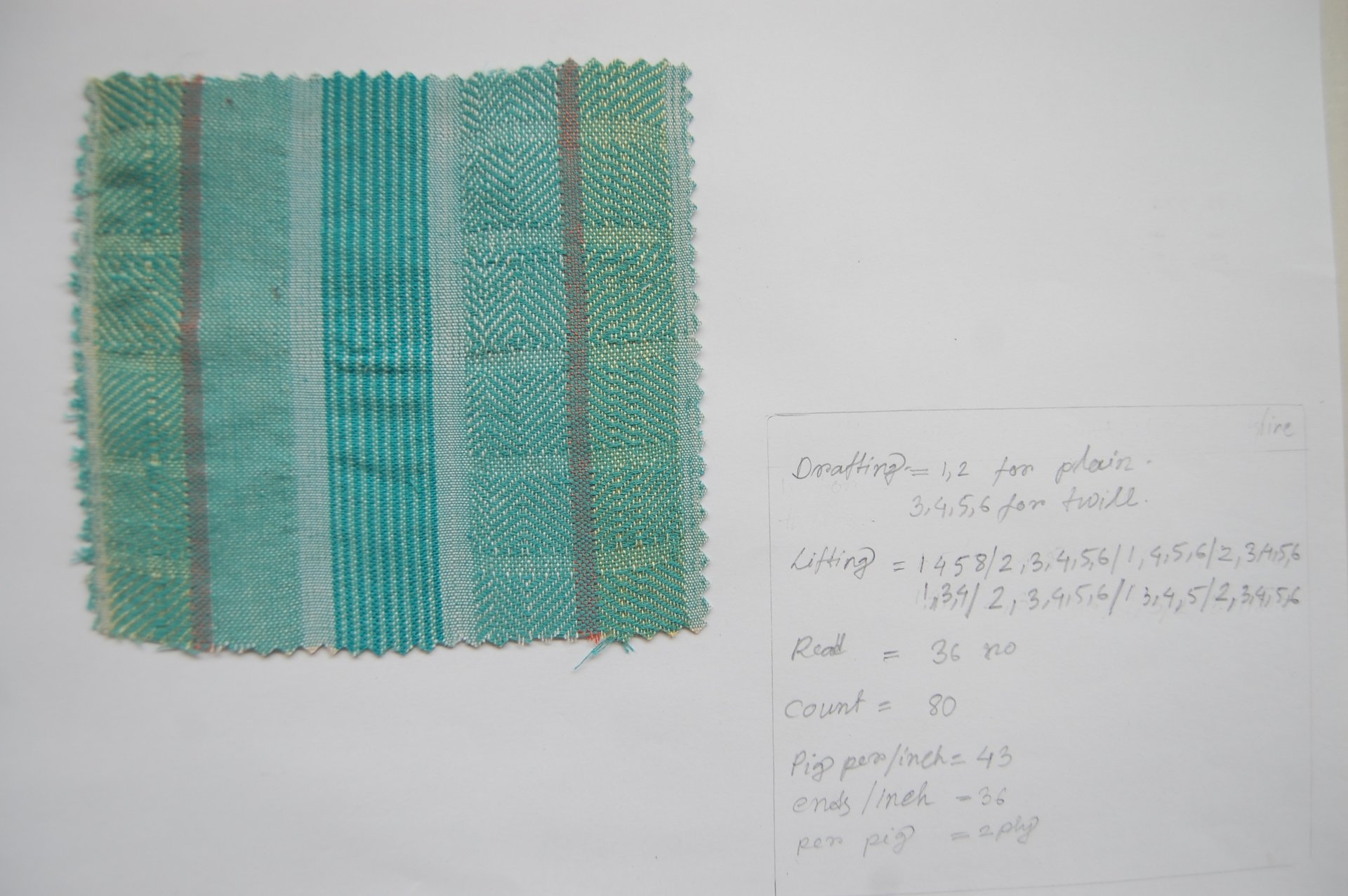

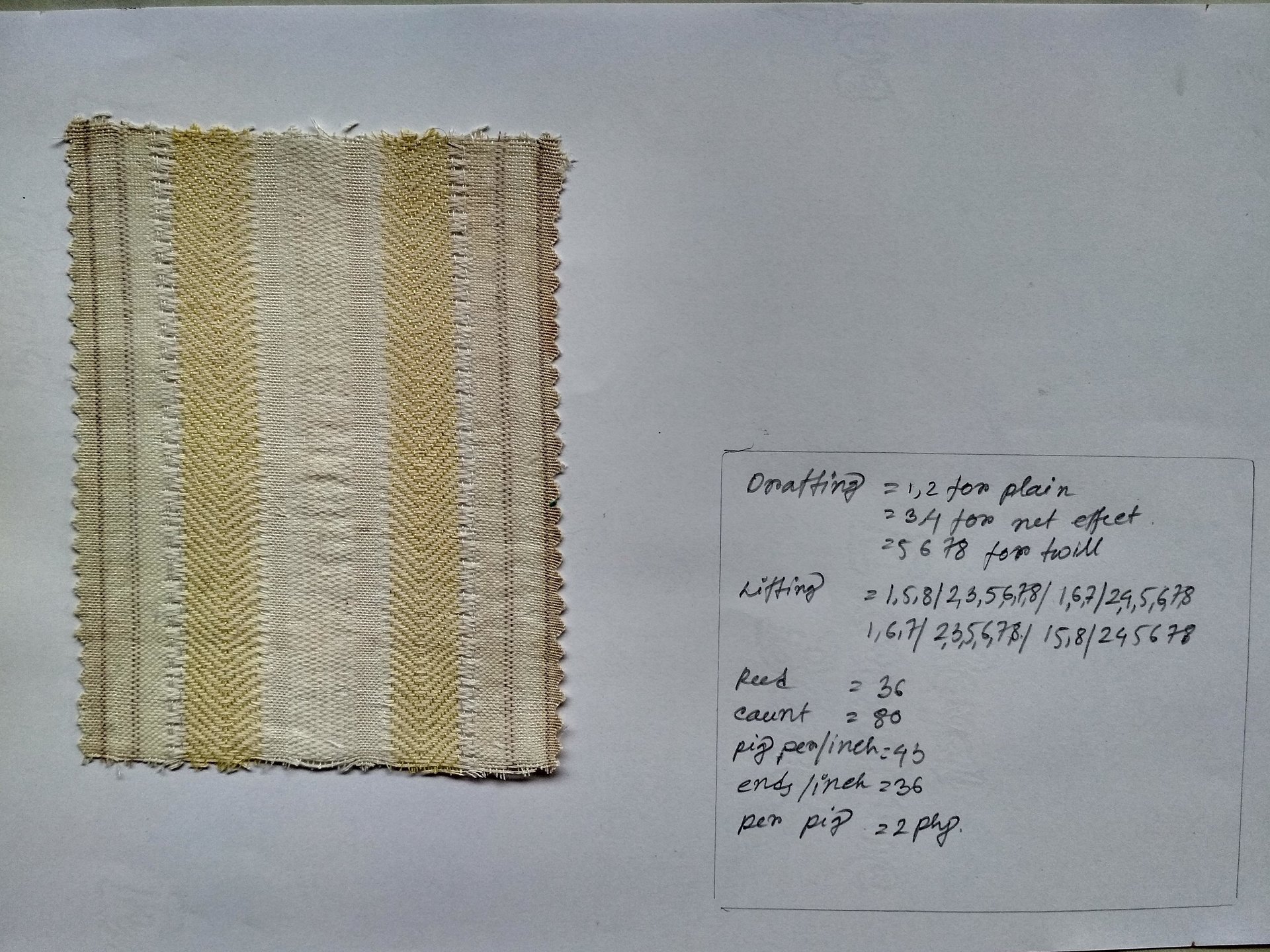

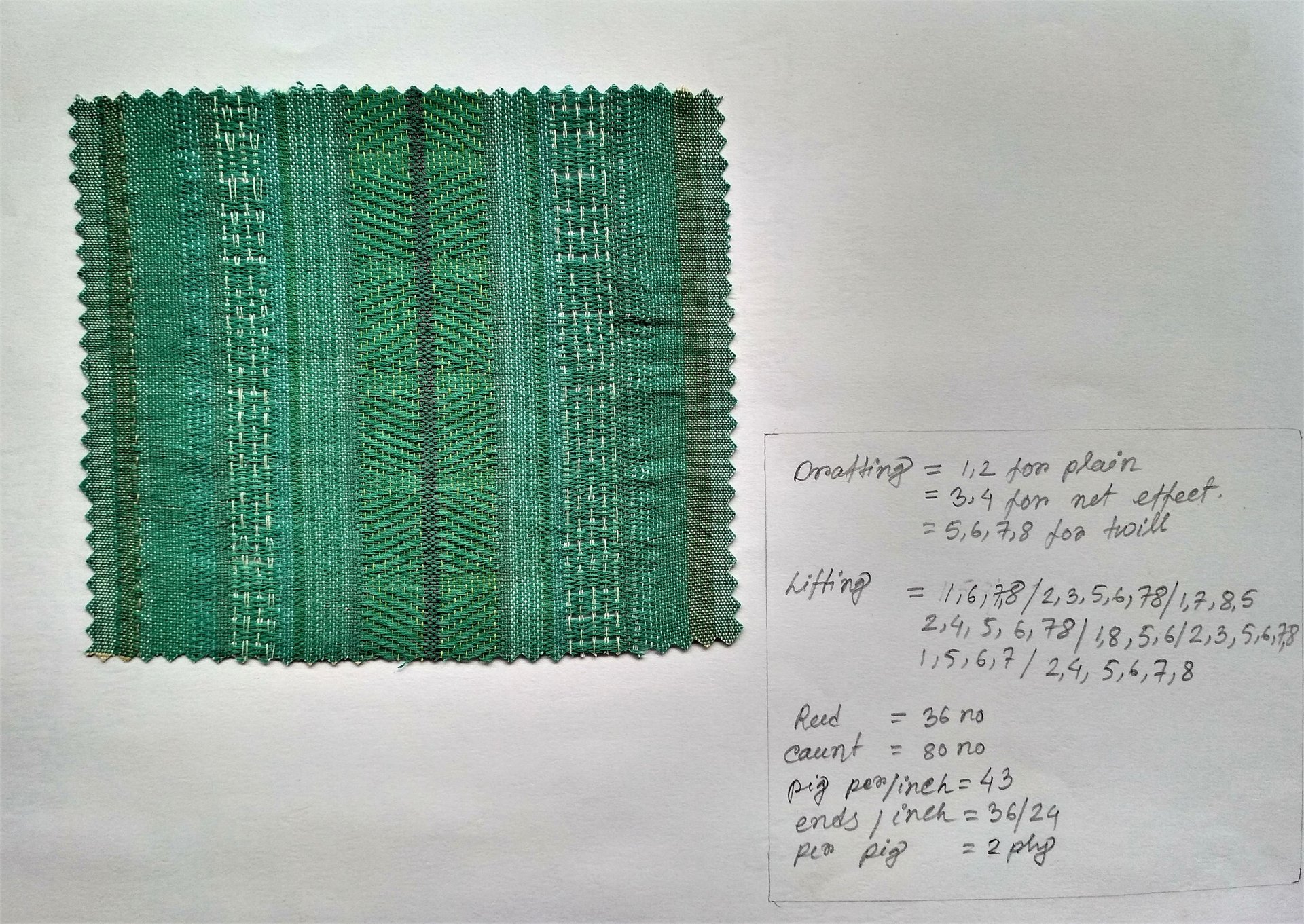

Size - variable (weaving cloth 12 x 10 cm)

(frame size 16 x 11 cm)

Year - 2018

process

click individual peace of image to get more detail understanding

Description

Every object inhabiting our environment carries with it an inherent form, presence, and materiality, contributing to the shaping of space that might otherwise appear void. In this work, the textile becomes more than a functional material; it asserts its own structural identity through the interlacing of threads, where warp and weft engage in a rhythmic choreography that defines both surface and substance. To explore this quiet transformation, I positioned a piece of woven cloth behind a simple glass of water. As the viewer shifts their vantage point, the refractive properties of the water begin to distort, magnify, and refract the textile's surface. This optical layering accentuates the intricacies of the weave—its textures, densities, and subtle irregularities—elements that often remain overlooked in casual observation.

The act of viewing through water becomes a metaphor for perception itself. Just as fabric, when draped upon the human body, transitions from a flat, two-dimensional plane into a sculptural, three-dimensional form, so too does the woven textile in this installation defy its conventional reading. The illusion of depth created through this optical device encourages a rethinking of the woven surface, not as passive or decorative, but as a dynamic agent of spatial transformation. In this interplay between thread, transparency, and light, the work offers a meditative inquiry into the nature of form, inviting the viewer to rediscover the hidden dimensionality of the textile. It becomes a dialogue not only between material and space but also between perception and presence, where the fabric reveals its potential to transcend its material boundaries.

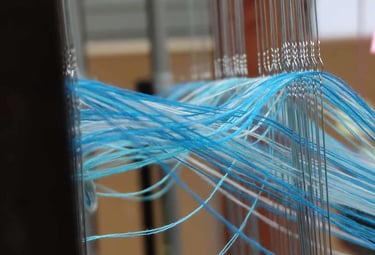

My relationship with weaving began long before I encountered it as an artistic medium. I spent much of my childhood at my mother’s ancestral home in Bengal, where my grandfather ran a handloom business during the 90s. The environment was filled with the rhythmic clatter of looms—three or four weaving looms often working at once—and the quiet presence of skilled weavers employed by my grandfather. In that region, weaving was not an isolated craft but an everyday ritual. Nearly every household in the surrounding area practiced it, especially for making fabrics like bedsheets. As a child, I perceived weaving as something so common and essential that it felt no different from fetching water or preparing a meal—an unremarkable yet vital part of daily life.

It was only years later, through my formal art practice, that these early experiences began to resurface—not as faded memories, but as foundational impressions. What once seemed ordinary took on new meaning. During my undergraduate studies in India, I began to explore weaving not just as a practical activity, but as a conceptual and structural process—an embodied language of form, memory, and labor. Though a small part of my weaving work continued during my time in China, nearly 90 percent of it remains grounded in India’s textile traditions, particularly those of Bengal, India.

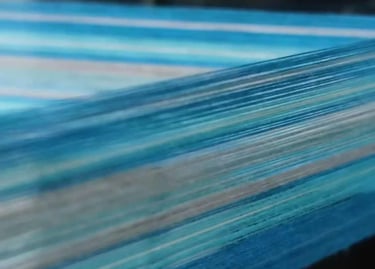

The process still fascinates me: how a single thread, through repetition, tension, and mathematical precision, becomes a self-supporting, architectural form. Weaving is more than a craft—it is cultural memory, structural knowledge, and emotional inheritance. As the dominance of mechanized looms has gradually displaced handloom practices, I find myself compelled to engage with this fading tradition, both as an artist and as someone returning to a personal history.

In my practice, weaving is both method and metaphor—a way to examine the intersection of everyday ritual and ancestral knowledge. Each thread carries with it stories of labor, loss, and resilience. It is through this threadwork that I continue to explore the quiet, overlooked architectures of the everyday, where structure and memory are inseparably entwined.